Thus, in 1941, Roald Dahl went home to England. He wasn’t there for long, though. Through his friendship with artist Matthew Smith, he became acquainted with some very important men in the British government. Dahl was a cultivated, forceful young injured pilot who seemed able to talk about anything. It wasn’t long before he was shipped off to the United States to help with the British War Effort as “assistant air attaché.”1

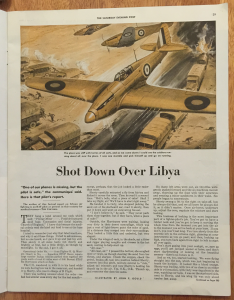

One of Dahl’s first duties in America was to get close to as many well-placed people as possible. Newspaper-owner Charles Marsh was one of these, and he and Dahl struck up an immediate friendship. Another duty was to help create a kind of British propaganda to keep America interested in the war and sympathetic to Britain’s effort. Famous English author C.S. Forester asked Dahl to tell him his own story, so that he could write it up. Dahl thought it easier to put something on paper himself, and the result was so good that Forester decided not to change a thing. The finished story appeared anonymously in The Saturday Evening Post in August 1942 under the title “Shot Down Over Libya.”

The story was introduced as a “factual report on Libyan air fighting” by an unnamed RAF pilot “at present in this country for medical reasons.” Of course, the “factual” part might have been a little bit of a stretch. As mentioned previously, Dahl’s crash was actually caused by lack of fuel and wrong directions, not from any enemy shooting. Much later, when this discrepancy was pointed out to him, Dahl claimed that the story had been edited and misleadingly captioned by magazine editors looking for a more dramatic tale.

As time passed and Dahl became more popular among Washington’s rich and famous, he became known for the wild yarns he would spin about his RAF adventures. He even wrote a story called “Gremlin Lore” about the mythical creatures that supposedly sabotaged RAF planes. Since he was a serving officer, Dahl was required to submit everything he wrote for approval by British Information Services. The officer who read it, Sidney Bernstein, decided to pass it along to his good friend Walt Disney, who was looking for War-related features for his fledgling film company. Disney decided to turn Dahl’s story into an animated feature called The Gremlins.

Problems immediately began to surface with the project. What did Gremlins look like? How could Disney copyright a name already known (and invented) by countless RAF pilots? Should the film be satirical or purely fantastic? Beyond these concerns, audience enthusiasm for the film began to wane as the War dragged on. Ultimately the project was scrapped, though Disney did put together a picture book in 1943 entitled Walt Disney: The Gremlins (A Royal Air Force Story by Flight Lieutenant Roald Dahl). This book, published by Random House in the United States and by Collins in Australia and Great Britain, is extremely rare and is considered a prize by any serious Dahl collector. It was his first book.

Footnotes

1. Some experts believe Dahl was secretly working as a spy for the British Secret Service under William Stephenson (“Intrepid”). Dahl himself boasted as much during interviews later in life. It’s an intriguing possibility.